James William Keys Parkinson was born in Shoreditch, London, in 1755. Medicine was his first passion, having trained initially with his father, and he published a great deal of medical texts during his career. He soon succeeded his father in running the family medical practice at 1 Hoxton Square. Many of his medical works were influential, discussing public health and welfare, and providing some of the earliest descriptions in English of afflictions like gout, appendicitis, and ‘Shaking Palsy’. This latter was the first comprehensive description of the disease’s symptoms and possible causes, and it was thus renamed Parkinson’s Disease almost fifty years after his death by Charcot. Parkinson had a very successful medical career, being elected a fellow of the Medical Society of London in 1787, and is known to this day for his role in understanding Parkinson’s Disease. However, during life he was well known for his contributions to fields outside of medicine, not least contemporary politics, in which he called for radical social reform and universal suffrage, often under the pseudonym Old Hubert.

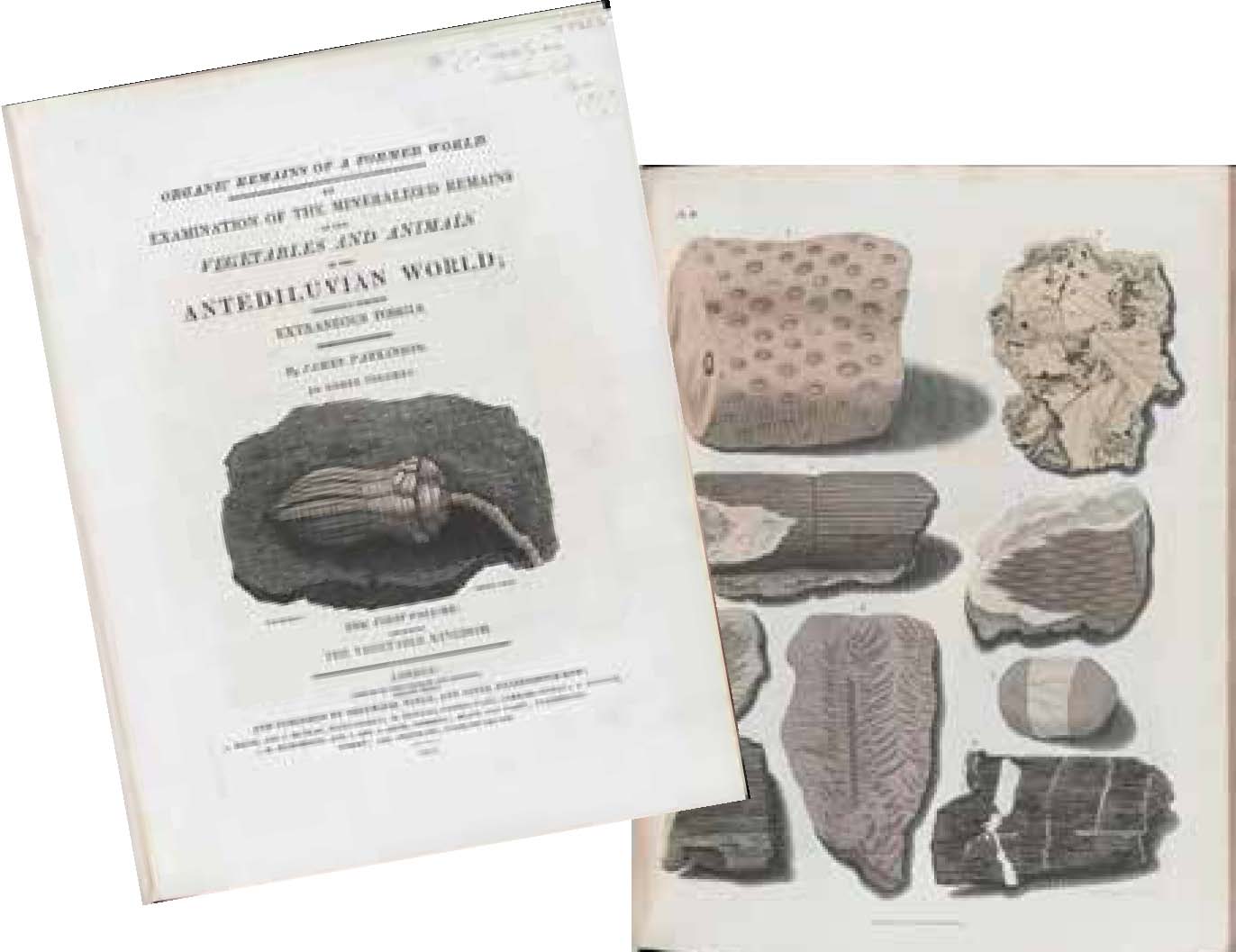

In the late 18th century, Parkinson began indulging an interest in collecting and illustrating fossil organisms. His key contribution to palaeontology was Organic Remains of a Former World, published during the early 19th century. Over three volumes, this contained his observations regarding fossils, accompanied by a number of beautiful plates hand drawn by him, and many coloured by his daughter. In Organic Remains, he discussed the history of palaeontology, preservation of organic fuels, fossil plants, fossil animals, and creationist theory. His works included incredibly extensive descriptions and classification of many groups. He figured a number of fossil echinoderms, molluscs, insects, reptiles, and mammals, describing in detail the morphology of these groups, and noting close similarities in some groups, like starfish, to modern counterparts. He also explained why certain groups, such as insects, are less likely to be preserved in the fossil record, and recognized the use of fossils in stratigraphy.

Rather than taxonomy, much of Organic Remains is dedicated to description and figuring of individual fossil specimens, their preservation, and referral to previous descriptions or modern comparisons. He published a subsequent book, Outline of Oryctology, which provided a shorter and more general overview of palaeontology. Parkinson firmly believed in the principle of catastrophism, which posits that the modern Earth has been shaped by large-scale cataclysmic events. In particular, like most scientists of the day, he believed in the Great Flood and that God controlled creation and extinction. However, he struggled to reconcile this with the concept of geological time. He did not believe that all of creation could have been accomplished in six days, so argued in his works that each day must therefore have lasted for much longer periods of time.