A PhD is generally a necessary step in the development of a career in academic palaeontological research, in either university or museum sectors. Most palaeontology PhD students express, at least at the start of their PhD project, the desire to build an academic career that allows them to conduct research. However, there exists widespread concern about how difficult a career path this is, and how few opportunities exist to obtain long-term academic jobs. These concerns are certainly not new: we had exactly the same concerns during and after completing our own PhDs over a decade ago, and between us we acquired well over a decade of postdoctoral and fellowship experience before we finally obtained our first permanent positions. However, the growth in social media over the last 5-10 years has perhaps amplified these concerns among students and made them more widely visible.

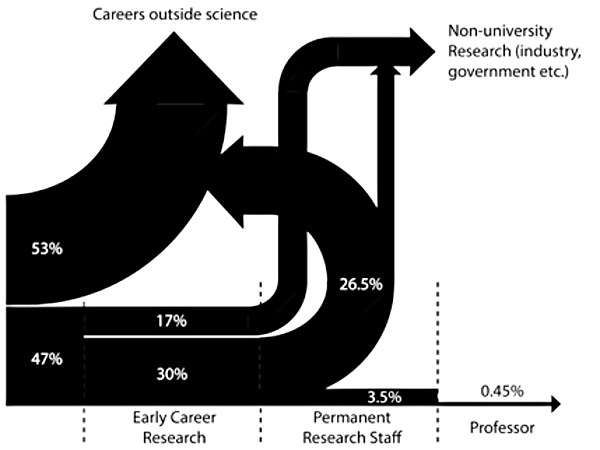

A 2010 policy document from The Royal Society[1] included a widely-reproduced diagram (Figure 1) that attempted to quantify career routes for those completing a PhD in science in the UK. It suggested that around 30% of PhD graduates go into ‘early career’ research jobs (e.g. postdoctoral positions), but that many subsequently move into industry or non-academic jobs, and that only 3.5% of PhD graduates ultimately build long-term careers as permanent academic research staff. They also estimated that just 0.45% of PhD graduates become full professors. (It is worth remembering that in the UK only c. 12% of university academic staff have the title ‘professor’ [2], differing from the situation in many other academic systems.) In late 2017, Nature ran an editorial[3] in which they suggested that only 3-4% of UK PhD graduates will find a permanent staff position at a university. Nature did not specify the source of this number, but it seems likely to be based on The Royal Society figure of 3.5%.

We have seen these very low numbers contribute to concerns about careers among PhD students on social media and in our own research groups. But we have suspicions about the applicability of these statistics to palaeontology for several reasons.

First, the Royal Society’s report did not provide detailed information on their methodology. Second, their results are aggregated across the whole of science, and may include fields that train large numbers of PhDs for industrial careers. We are unaware of any previous attempts to estimate comparable values specifically for palaeontology. Third, based on our own experience the numbers seem implausibly low. They suggest that only 1 in every 29 palaeontology PhD students trained will go on to a long-term academic career, and that only 1 in every 222 palaeontology PhD students trained will become a professor. This would imply that the University of Bristol Palaeobiology Group, for example, would need to train 1,332 PhD students merely to replace the six professors currently listed among its staff members[4]. In fact, the Bristol Group list 42% of 144 PhD graduates since the late 1980s as having obtained permanent academic positions[5], an order of magnitude higher than the Royal Society data. Is this example really so unrepresentative? To answer this question, broader palaeontology-specific data are needed.

Also of interest to us is the gender balance between those who successfully pursued academic careers after graduation, and those who chose, or were forced, to work outside academia. This is because there is clear evidence that there is a ‘leaky pipeline’ in academic careers for women[6],[7], meaning that proportionately fewer women go on to academic jobs than men. Initiatives such as the Athena Swan Charter[8] have been widely adopted across the higher education sector to attempt both to recognize and to rectify this problem. The Palaeontological Association has recently launched a diversity survey[9] and has started a mentoring scheme for academics and PhD students[10] in an attempt to identify and address some of the reasons that might make women (and other under-represented minorities) leave academia. But is there evidence to document the existence of a ‘gender problem’ in palaeontology? We suspect that there is, based on our own experiences. However, to our knowledge, little data exists to support such a claim.

Getting accurate data on long-term career pathways for palaeontology PhD graduates is challenging. Ideally, one would ask all academic departments that have historically trained palaeontology PhDs to provide details of their students, and then trace the subsequent careers of those individuals. Such information may not be available, however, or departments may be unwilling or unable to share it. Here, we use an alternative approach that represents a relatively crude first attempt at tackling this problem. Progressive Palaeontology is an annual conference sponsored by the Palaeontological Association, organized by PhD researchers within the UK palaeontological community, with the majority of presentations being made by PhD students (and to a much lesser extent, at least historically, by MSci, MSc and undergraduate students). It has been running for over thirty years, likely captures a relatively representative snapshot of the UK palaeontology PhD community in a particular year, and abstract volumes or meeting reports are readily available for most meetings. Thus, we decided to use the presenters at Progressive Palaeontology for the years 2000–2008 as our list of palaeontology PhD students, and track them through to the present day to get an estimate of those who remained in academic careers. This time span begins at the start of the 21st century and ends ten years prior to the present day, as we felt that ten years after attending Progressive Palaeontology should represent a substantial enough period of time to assess career prospects.

The data

Although the issues that we discuss affect palaeontologists worldwide, our data can only address career prospects in the UK and Ireland. They represent a preliminary attempt to address these questions, and we recognize that the situation in other countries and academic systems might be very different.

We collated presenters at all Progressive Palaeontology meetings from 2000 to 2008, recorded the gender they identified as at the time, whether or not they were a PhD student, their institutional affiliation, their sub-discipline (coarsely characterizing individuals as belonging to vertebrate palaeontology, invertebrate palaeontology, palaeobotany, micropalaeontology or other), whether or not they are still in academia, and if not, their current career. We collected data about presenters from Google Scholar Citations, LinkedIn, Facebook, web searches, and our own knowledge or that of colleagues. We were unable to obtain all data for all presenters, particularly regarding the current careers of those who left academia and whom we do not know personally. We were able to find more data on presenters at more recent meetings, probably because of the widespread adoption of social media in the latter half of the time frame of our study. We defined ‘still in academia’ as those who had published a research paper in any academic discipline (not necessarily palaeontology) since 2016 and who appeared to be either currently or recently (since 2016) employed in an academic position in a university, museum or research institute. We excluded presenters who we could identify as having been MSc or MSci students and who did not go on to do a PhD in the UK or Ireland in palaeontology. We also excluded presenters registered for PhDs outside of the UK or Ireland, even if they subsequently worked in the UK or were British or Irish, on the basis that we were primarily interested in the career paths of PhD students in the UK and Ireland. Several students presented at more than one Progressive Palaeontology; we only counted each presenter once, at their first meeting, and excluded them from later meetings. The resulting dataset comprises 94 unique presenters from 27 institutions over the nine meetings, 43% of whom were identified as female and 57% of whom were identified as male. 41% of presenters were invertebrate palaeontologists, 34% were vertebrate palaeontologists, 11% were palaeobotanists and 9% were micropalaeontologists, with the remaining 5% belonging to other sub-disciplines such as ichnology or sedimentology.

Long-term employment prospects in palaeontology

Of the 94 presenters, 41 (44%) are still in academia according to our definitions. This percentage is higher than the Royal Society’s estimate of 30% of science PhD students going into ‘early career’ academic positions, and an order of magnitude greater than the 3.5% of scientists the Royal Society estimated attain permanent jobs. It is in line, however, with the Bristol Group data, suggesting that the career outcomes of their graduates are not misrepresentative of the discipline as a whole. We have not attempted to assess which of our presenters have permanent jobs, for the following reasons: (1) it is difficult to ascertain the nature of an individual’s contract from their web profile; (2) there are a variety of different routes into academia, some of which never result in a ‘permanent’ contract, for example some research fellow positions; (3) some of the individuals in our study are postdocs who may have permanent jobs in the future. Despite this, it seems clear that nearly half of the PhD students who presented at Progressive Palaeontology are still employed in the field and publishing at least ten years later, leading us to conclude that the prospects for medium- to long-term employment in palaeontology for UK and Irish PhD students are better than often suggested.

Does palaeontology suffer from a ‘leaky pipeline’ for women?

The picture is less positive, however, when we examine the gender breakdown of those still in academia. Just 20% of female-identified PhD students who presented at Progressive Palaeontology are still in academia at least ten years later, in contrast with 61% of male-identified PhD students, indicating that females are leaving academia in droves. There are a number of widely-cited reasons that women may leave academia[11],[12]; however, there currently exists no palaeontology-specific data.

We investigated gender differences among the sub-disciplines in order to discover whether this gender disparity was being driven by women in a particular field. Thirty-two of the presenters at Progressive Palaeontology from 2000 to 2008 were vertebrate palaeontologists and 66% of them are still publishing. Of these presenters, 31% (10) were female and 69% (22) were male. Three of the ten female presenters (30%) are still in the field. In contrast, a staggering 82% of male presenters (18) are still active researchers. Indeed, only four male vertebrate palaeontology students who presented at Progressive Palaeontology between 2000 and 2008 have left the field, and of those, three still regularly attend conferences and are thus part of the broader community even if they are not employed within academia.

Unfortunately, the data suggest that female invertebrate palaeontologists are even less likely to have a long-term career in academia than their vertebrate palaeontology counterparts. Thirty-nine invertebrate palaeontologists presented at Progressive Palaeontology between 2000 and 2008; 49% (19) were women and 51% (20) were men. Just 21% (4) of the women remain in academia, in contrast to 55% (11) of the men. It appears that invertebrate palaeontology has a lower retention rate than vertebrate palaeontology overall, but the prospects for female invertebrate palaeontologists are particularly poor. Among the nine women who presented in the sub-disciplines of palaeobotany and micropalaeontology combined, just one remains in the field.

The difference in the retention rates of female and male palaeontology PhD candidates is shocking, and we must urgently examine what is leading to so many women leaving our field.

Alternative careers for PhD palaeontologists

Our data on the careers of those who left academia are sparse, but the most common jobs among our sample are in museums, teaching or publishing. Many of these career paths still represent an active and substantial contribution to the palaeontological community, but do not include the research component that has been the primary focus of our analysis.

Final thoughts

Early career palaeontologists have been despondent about the academic job market for as long as we have been in the field (and probably long before that), and yet our data suggest that prospects for PhD graduates to build an academic career are better than they are often portrayed. We believe that the last ten years have seen a substantial growth in the number of academic positions held by palaeontologists at universities in the UK, and this appears to have come about both through growth in numbers of palaeontologists at universities where the subject has long had a strong presence (e.g. University of Manchester, University of Leeds, University of Birmingham), but also through palaeontologists gaining positions in academic departments that have limited or no previous tradition in the subject (e.g. University of Brighton, University of Lincoln, University of Salford, Manchester Metropolitan University). Quantifying this apparent pattern and its potential drivers goes beyond our scope here, but we see no reason to suspect that this trend will stop in the immediate future, particularly with the Research Excellence Framework 2021 (and its inevitable linked upturn in recruitment) rapidly approaching.

Our message is less positive when it comes to prospects for women. Our data concern those entering PhDs ten or more years ago, and the situation and career chances for women may have improved over the last decade. But this clearly represents an area where we as a community need more data to better understand the barriers to career progression for women, and where we need to do more to support our female students, postdocs and academics. We applaud the initial steps that the Palaeontological Association is making to address this issue.

We strongly believe that those thinking of starting PhDs should receive realistic information on career prospects in academia, and be made aware of alternative career paths. Our admittedly imperfect dataset suggests that roughly half of UK palaeontology PhD students will still be engaged in academic research ten years after finishing their PhDs, and we consider that a reason to be positive about the long-term future of our discipline.

Reference

Alper, J. 1993. The pipeline is leaking women all the way along. Science, 260, 409–411.

[3] https://www.nature.com/news/many-junior-scientists-need-to-take-a-hard-look-at-their-job-prospects-1.22879

[7] Alper (1993).

[9] https://www.palass.org/association/diversity-study; see also Fiona Gill’s update on this study elsewhere in the issue

[10] https://www.palass.org/publications/newsletter/palaeontological-association-needs-mentors; see also Emily Rayfield’s update on this programme elsewhere in the Newletter issue.